In the nearly four decades since its publication, Manufacturing Consent: The Political Economy of the Mass Media has solidified itself as one of the most incisive critiques of American journalism. Noam Chomsky, the linguist turned political dissident, and Edward S. Herman, the late economist and media analyst, do not merely argue that the press occasionally fails in its duty to inform the public. Rather, they propose something more unsettling: that corporate and state interests shape mainstream news coverage so systematically that “objective journalism” often serves as an instrument of power rather than a check upon it.

Their now-famous “propaganda model” outlines the five structural filters through which information passes before it reaches the public: corporate ownership, advertising revenue, sourcing biases, flak (disciplinary actions against dissenters), and a shared ideological enemy (once Communism, now terrorism or authoritarian adversaries). This model is not merely an academic framework; it is a theory that lands with damning clarity when applied to historical and contemporary media coverage.

Chomsky and Herman illustrate their argument with forensic precision, comparing the Western press’s treatment of atrocities committed by U.S.-backed regimes with those carried out by officially designated enemies. For instance, they contrast coverage of Indonesia’s brutal invasion of East Timor—met with near silence in American media—with the outcry over Communist Vietnam’s intervention in Cambodia, despite the latter having a clearer humanitarian rationale. The authors are at their best when they wield raw data: column inches, headline placement, and the language of reporting become empirical evidence for a deeply ingrained bias.

For readers unaccustomed to Chomsky’s methodical dismantling of official narratives, the book can be daunting. It is not a work of rhetorical flourish or literary style; its prose is dense, meticulous, and unforgiving in its demand that readers follow its logic to its disturbing conclusion. Some critics have dismissed Manufacturing Consent as reductionist, arguing that it leaves little room for journalistic agency or the possibility of genuine investigative breakthroughs. Others have pointed out that, while the book critiques corporate media, it gives less attention to alternative media ecosystems, which have evolved dramatically since its first publication.

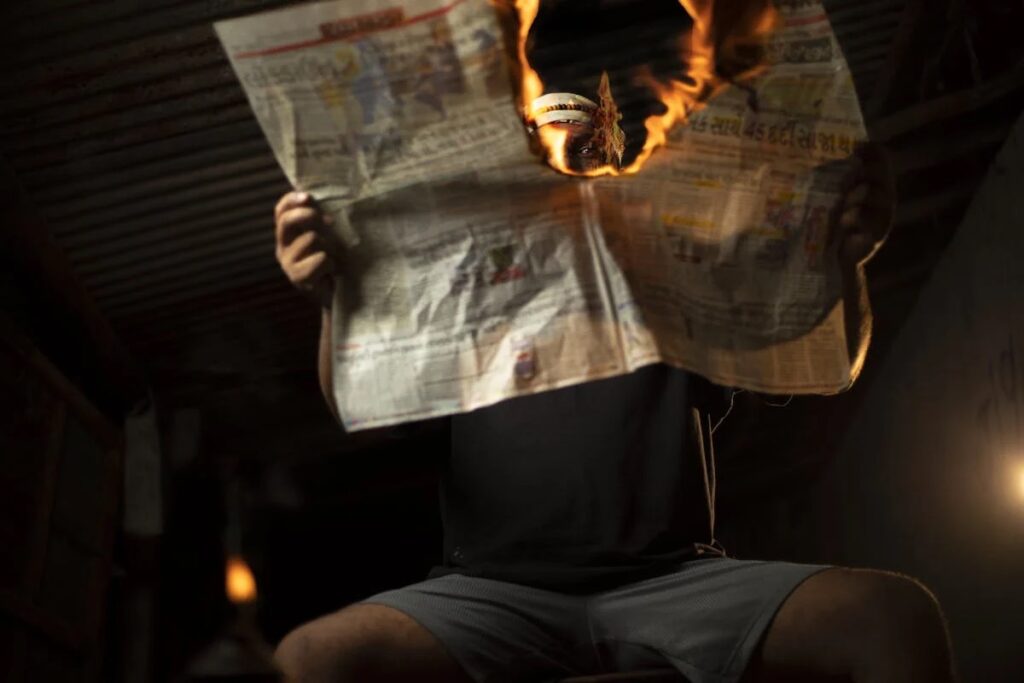

And yet, as American news has grown ever more polarized, with mainstream outlets contorted by economic pressures and partisan allegiances, Manufacturing Consent feels more relevant than ever. Whether it’s the breathless deference to official sources in wartime reporting or the algorithmic curation of news that reinforces ideological silos, Chomsky and Herman’s thesis continues to reverberate in an age when information itself has become a battleground.

This is not a book that flatters its readers or offers easy solutions. It is, however, an indispensable one—both a masterwork of media analysis and a warning against the complacency that allows power to shape perception.