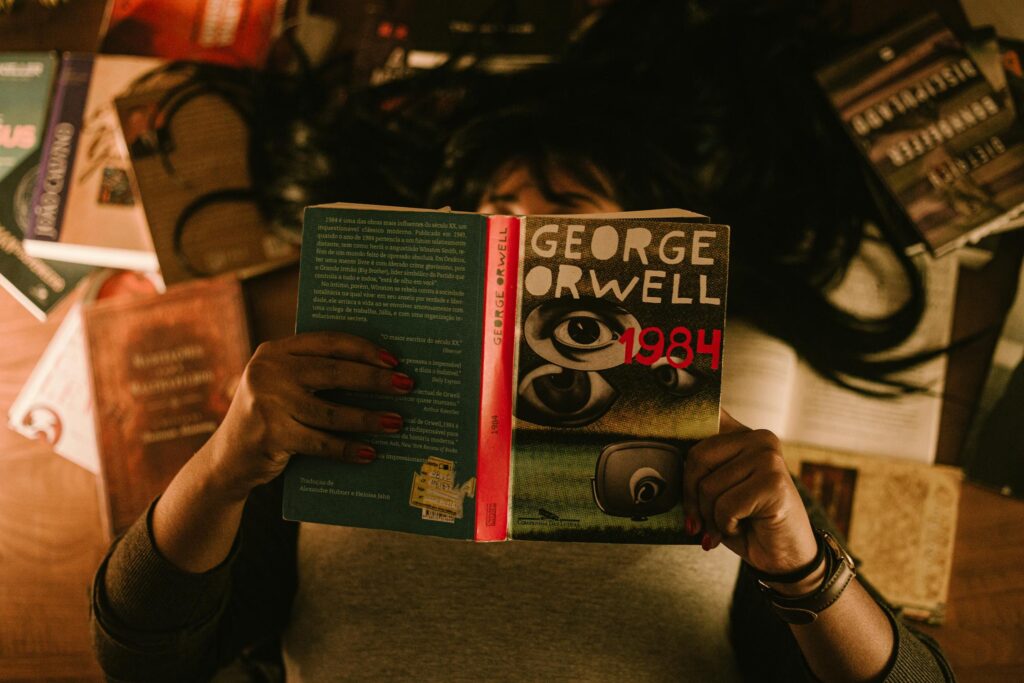

Revisiting 1984 today feels less like reading a novel and more like stumbling upon an old prophecy that’s somehow still unfolding. George Orwell’s bleak vision of a world where truth is whatever the powerful say it is has never gone out of print, and for good reason. The book doesn’t just predict totalitarianism—it dissects the way power twists reality, turning people into willing participants in their own oppression.

Yes, 1984 gave us Big Brother, Newspeak, and the Thought Police, terms that have seeped so deeply into our cultural consciousness that they’ve almost lost their bite. But the real horror of the novel isn’t just surveillance or censorship—it’s the way Orwell shows language itself being reshaped to make resistance impossible. When words are stripped of meaning, when history is rewritten on demand, what’s left to hold onto? Winston Smith, the novel’s tragic protagonist, fights against this erasure, clinging to the idea that truth still exists. But Orwell is merciless: in the end, Winston’s rebellion doesn’t just fail; it’s absorbed, repackaged, and used against him.

What makes 1984 so chilling is how familiar it feels, no matter when you read it. Orwell was writing in the wake of World War II, disillusioned by Stalinism and the way political ideologies could bend people into submission. But he wasn’t just writing about Soviet Russia or Nazi Germany. He was writing about the way power operates everywhere—how it rewrites history, controls language, and convinces people to accept the unacceptable. It’s a warning, not about one specific regime, but about human nature itself.

And that’s why the book remains essential. Orwell understood that oppression isn’t always loud and violent; sometimes, it’s quiet and bureaucratic. Sometimes, it looks like convenience. A world where people willingly hand over their privacy, where history is rewritten in real time, where questioning the official narrative makes you a social outcast—that’s not some distant dystopia. That’s the world we already live in.

The most disturbing part of 1984 isn’t its grim ending or its depiction of a world without freedom. It’s the way Orwell makes it clear that none of this happens overnight. The slow erosion of truth, the normalization of doublethink, the willingness to accept absurdity because it’s easier than resisting—it’s all a process. One that we, in many ways, are already participating in.

There’s a reason people keep turning to 1984 whenever the world starts feeling unhinged. It’s not just a novel—it’s a mirror. And what’s staring back at us isn’t particularly reassuring.

Join us in making the world a better place – you’ll be glad that you did. Cheer friends.